search for a Trip

The Forbidden City stands as a testimony to past glory that informs contemporary people about Chinese civilization's advanced thought and practices across six centuries, Wang Kaihao reports.

Editor's note: The Forbidden City is celebrating the 600th anniversary of its completion this year. China Daily journalists speak with historians, researchers and experts to discover how this architectural wonder that embodies traditional Chinese thinking evolved over time and its vital role in East-West communications.

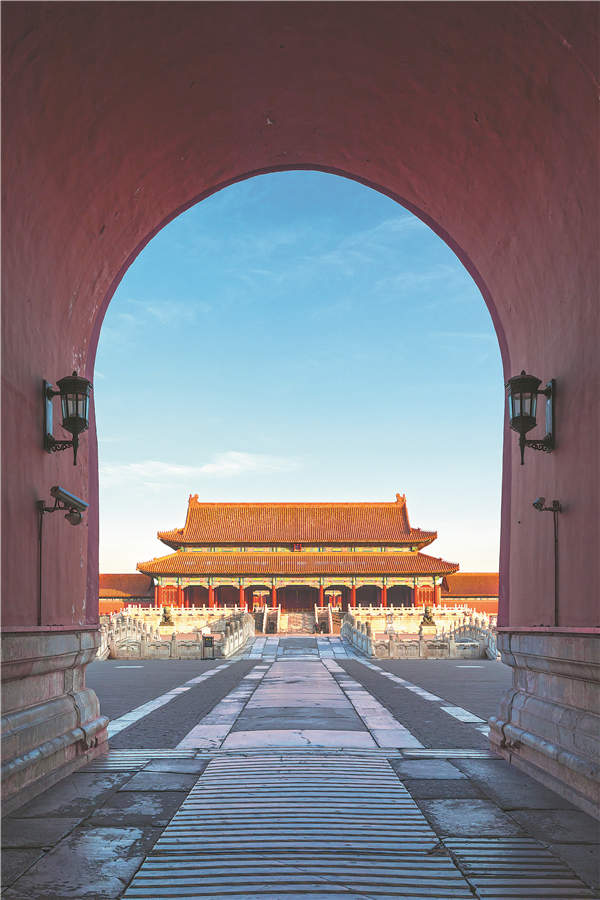

If the millennia during which China built and renovated palaces is viewed as an epic, Beijing's Forbidden City is an awe-inspiring final chapter.

The previous pages of this story may have been marvelous. But they're at least partially, if not largely, lost to the rise and fall of many dynasties, leaving behind ruins that serve as archaeological puzzles that experts are still putting together.

But in the heart of Beijing stands a 720,000-square-meter palace complex made of wood and earthen bricks, the largest surviving specimen of its kind in the world.

And this compound, which served as the imperial palace from 1420 to 1911, where 24 emperors once lived, is celebrating the 600th anniversary of its completion this year.

For this special moment, the Meridian Gate Galleries by the museum's entrance have become a "lobby "to receive visitors to the ongoing exhibition, Everlasting Splendor: Six Centuries at the Forbidden City, which will run through Nov 15.

"There are so many things to talk about within 600 years," says Zhao Peng, director of the museum's architectural heritage department, who is also the exhibition's main curator.

"It's better to focus on the 'city'-that is, the architecture-to see how this place formed and evolved … It's the crystallized wisdom and talent of the ancient Chinese."

Still, it's not easy to select just 450 items, including construction components and emperors' relics, to unfurl a panoramic picture of architectural glamour.

Eighteen landmark years during the six centuries of history have been chosen to highlight the exhibits in chronological order to show how the compound was born, grew up and matured.

"From these slices of time, we can see the bigger historical picture," Zhao says.

In 1406, Zhu Di, the third emperor of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), proposed moving the national capital from Nanjing, capital of today's Jiangsu province, to Beijing, where he once resided as a prince and could better safeguard the northern frontiers.

The complex was completed in 1420, after about 10 years of preparation and a massive three-year construction. The capital was officially relocated the next year.

"An amazing feature of the Forbidden City is that it rigidly follows certain formats no matter how times changed," Zhao says.

"This reflects traditional Chinese thought that emphasizes rituals and the harmony between humans and the heavens."

The Forbidden City was built following rules inherited throughout Chinese history.

As the exhibition shows, Kaogong Ji (Book of Diverse Crafts), a Spring and Autumn Period (770-476 BC) publication about craftsmanship, included in the fundamental Chinese classic on the rituals of organizational theory, Rites of Zhou, spells out the basics for palace construction.

It regulates a symmetrical layout for capital cities, which should be centered by a palace with a north-south axis.

The historical areas of today's Beijing, including the Forbidden City, precisely echo the rule.

"Finally, this ideal plan, which has been referred to for 2,000 years, reached its zenith when it was perfectly practiced in Beijing," Zhao says. Rites are represented through architectural details.

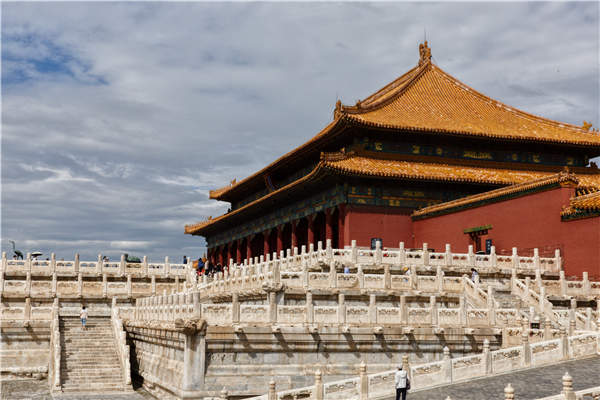

For example, only the Hall of Supreme Harmony (Taihe Dian), the palace's highest-status building, where the most important ceremonies took place, can have 10 deified creatures as ornaments on the roof.

The fewer the roof ornaments, the lower the building's rank.

And the hall also has 11 "rooms "on its facade, the most in the complex. (In ancient Chinese architecture, a "room", or jian, refers to a quadrangular indoor space between four pillars.)

The shape of the roof is another key indicator of a building's status. For example, Taihe Dian's roof adopts a pattern called chongyan wudian-a double-eave hip roof with curved and protruding edges-the design exclusively reserved for the highest-level structures.

In 1734, Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) Emperor Yongzheng released official guidelines for palace-construction formats. The more than 2,700 page book comprehensively regulated architectural criteria like pillar sizes and rooftop decor, which Zhao says is a benchmark of integrating rites with Chinese architecture.

Beijing's Forbidden City has two older cousins.

When Zhu Yuanzhang established the Ming empire, the ambitious emperor initially located the imperial city in his hometown in today's Fengyang county, Anhui province. But construction on the grand complex stopped abruptly for unknown reasons. He decided to instead build an imperial city in Nanjing.

Both imperial cities are in ruins but still offer some key findings, such as stone rails and tiles in the Meridian Gate Galleries, which indicate what the earliest architecture of the Forbidden City may have also looked like.

"Although the Forbidden City's basic layout remained the same, it was constantly being rebuilt and renovated throughout its imperial years," Palace Museum architecture researcher Zhang Jie says.

For example, the Hall of Supreme Harmony was swallowed by flame less than a year after its completion. It was rebuilt several times throughout history. The current hall was built in 1695, during the reign of Emperor Kangxi (1654-1722).

Before the invention of the lightning rod, the only way to combat the heaven-sent strikes was with prayers.

Among the roof ornaments, a thunder god is unique to Taihe Dian. Such an ornament is also exhibited for people to examine more closely.

Ancient artisans knew that more practical fire controls were needed. Firewalls have stood by the two wings of today's Taihe Dian since the 1695 rebuild. An exhibited Ming painting shows there were previously two wooden corridors.

"We've seen many references in paintings that indicate buildings' original appearances," says Di Yajing, deputy director of the museum's department of architectural heritage.

"However, we need further investigation, archaeological research and the study of documents to see if these paintings accurately match historical facts."

Some folk legends say Li Zicheng, a rebel leader, burned down the entire Forbidden City in 1644, marking the fall of the Ming Dynasty.

This has led many among the general public to believe that most key structures were rebuilt during the Qing Dynasty, but academic research indicates the opposite.

"The wooden frames of many Ming buildings are still very well preserved," Di says.

"And some buildings have Ming foundations but Qing roofs. It's difficult to judge which dynasty a building is from. Periodization is a complex procedure that needs detailed research of the beams, styles of colored decorations and building materials."

No matter how their ancestors' rules were passed down, it's understandable that successive emperors desired to decorate their new home.

"Ming emperors preferred simple but grandiose appearances. So, buildings were larger then. But their Qing counterparts preferred more exquisite aesthetics," Di says.

Sometimes they had to, as it could be difficult to find giant pieces of timber from precious trees during the renovations. But they also wished to demonstrate their wealth and regal status through state-of-the-art craftsmanship.

Emperor Qianlong (1711-99), who adored fine arts, pushed the trend to a peak. In 1776, he ordered the construction of the Palace of Tranquil Longevity (Ningshou Gong) as a potential resort for when he'd retire. Its garden became a trove of exceptional interior decorations.

A displayed lacquered gauze that was once set on a window enables visitors to glimpse its extravagance, as the garden has never been opened to the public.

The silk piece also mixes papercuts, gilding, dyeing and lacquering, which means it required extraordinary cooperation among several artisans. The 12-layer gauze is as thin as a sheet of paper.

"We've tried to duplicate it but failed, despite today's advanced manufacturing," Di says. "This lost technique reminds us to take good care of our cultural heritage."

A comprehensive renovation of key buildings in the complex has been underway since 2002.

Although it was originally planned to be finished for this milestone anniversary, architectural experts ultimately decided to slow down and ensure they were acting in a responsible manner and respecting the history.

Everlasting splendor, it seems, may refer to not only physical structures, but also the desire of those working hard to maintain the legacy of our ancestors.

More Attractions